This time we fly to the Netherlands by plane. We easily manage to get to the town of s’Gravendeel, but there we discover that there is no bus to our village on Sundays. A ten-kilometer walk with a two-and-a-half-year-old child and luggage doesn't appeal to us much. Fortunately, an elderly gentleman takes pity on us and gives us a ride to the port itself.

We discover that the most reliable means of transportation here is the bicycle. In the Netherlands, renting a bicycle with a child seat poses no problem. We also get the largest bicycle panniers we've ever used and head to the local Lidl for groceries.

Our aged yacht was "stained" from the beginning. We could not remove the shades of yellow and brown from the gelcoat, despite using various recommended products at different locations. Only in Strijensas were we advised to use a product that made the hull white again - oxalic acid.

While spending a lot of time operating the engine, we also learned something quite simple and likely obvious to many people: how to operate our new VHF radio model. Previously, we used a radio with a Bakelite handset, similar to that of an old landline phone. However, our new radio has a speaker and a pear shaped microphone. Initially, we had considerable difficulty listening to correspondence while the engine was running, especially when the helmsman himself was handling it from the cockpit. It was only after some time that we realized the microphone also had a small speaker built-in, and depending on whether we were transmitting or listening, we either held it to our ear or spoke into it. So, it essentially performs the same function as the previous handset.

Cruising in rivers and canals was generally pleasant and safe, but we realized how careful one must be around barges in such places. We observed these boats unloaded, with the side protruding 3-4 meters above the water's surface, and loaded, with less than a meter above the surface – this made us aware of the immense weight of such a barge. The inertia of such a unit is huge, and if it encounters a current or eddy, it can indeed be seriously swayed. Once, we almost got hit by such a giant - the captain saw what was happening, but gestured for us to flee, as he could do nothing.

Soon, we left the hospitable waters of the Netherlands and continued further west. We planned two stops in Belgium, but the wind was so favorable that we sailed directly to Nieuwpoort. There were no famous local fries, but we bought a fishfinder. The old one had been damaged, and it was greatly missed.

Reaching France, we made a small faux pas—upon approaching the port, we realized that we didn't have a French flag to hang under the spreader. We felt all the more embarrassed because the French harbor master greeted us with a Polish "Dzień dobry!" Right after docking, we rushed to the nearest store and corrected the oversight. Later, we had many opportunities to confirm that the belief that the French don't speak English is false. Our French is limited to pardon, merci, and s'il vous plaît, yet we managed to communicate easily everywhere. The locals, and not just those who make a living from tourism, showed genuine kindness.

We rest for one day in Calais. There is a fairly well-known modern art museum there, but contemplating art in the company of a two-and-a-half-year-old child is really difficult. Despite the not-so-good weather, we head to the beach where Kamilka delightfully digs in the sand. In Boulogne, we come across the Sea Festival. There are numerous attractions, and we find some fun activities for the Young One. In the biologists' tent the parents learn what skate eggs look like.

On July 12th we reach Dieppe.

The marina is large, so walking from our parking spot to the captain's office is quite a stroll.

On the way, we pass a boat that someone left on the water for an extended period without supervision - the sight somewhat chills us - even though the yacht was originally well moored, some lines have chafed, and the boat has banged against the dock for so long that a hole the size of a fist has formed in the bow. We previously considered leaving Stubborn on the water, but now we are glad we found a place where our yacht can stand on land.

The city itself makes a very good impression on us - the stone streets are bustling with life, as we happen to arrive during the market. We purchased a piece of regional cheese and a fish, which the gentleman gutted for us on the spot, throwing the insides to the seagulls. The birds swooped down, which elicited wild enthusiasm from Kamilka. Then the man started deliberately picking out smaller fish from his stall and throwing them to the birds just to give our kid some pleasure. In great spirits, we returned to the boat to enjoy our purchases.

We sail from Dieppe to Le Havre and then to St Vaast.

We leave France and head to the Channel Islands. We stop at the buoy near the village of Omonville-la-Rogue, to set off the next morning to the island of Sark, which we only view from the anchorage. Although it is just 32 km from the French coast, Sark is subject to the British Crown. Until 2008, it was the last feudal state in Europe, but under the influence of millionaires, the Barclay brothers, its system changed to be slightly more democratic (although many of the laws affecting its 500 residents still originate from the Middle Ages).

Around the Channel Islands, the tidal currents are so strong that at one point, we were motoring and sailing, yet for about an hour, we were moving backward. Caution is advised!

The next day, we dock in Guernsey. Since it is not part of the European Union, before we can go ashore, we must go through immigration procedures - the yacht raises a yellow Q flag and waits for an official. It all sounds intimidating, but the procedure turns out to be quite quick, and the harbor staff are friendly. Although these islands are not formally part of the United Kingdom, being merely Crown Dependencies, we are greeted by quintessentially English weather – temperatures in the teens and drizzle. This did not hinder the Guernseymen from celebrating the Harbour Carnival. There were many diverse events.

We are watching a rubber duck race, tug-of-war over the port entrance (the losing team falls into the water), and a flying contest on makeshift vehicles - contrary to the name, flying is the least significant part of the show - the costume and spectacular dive into the water are the most important. Zuza likes the team dressed as seagulls and fries the most, but the competition is truly fierce. We are also participating in breaking a Guinness record. We are part of the longest chain of people standing one behind the other and patting each other on the back.

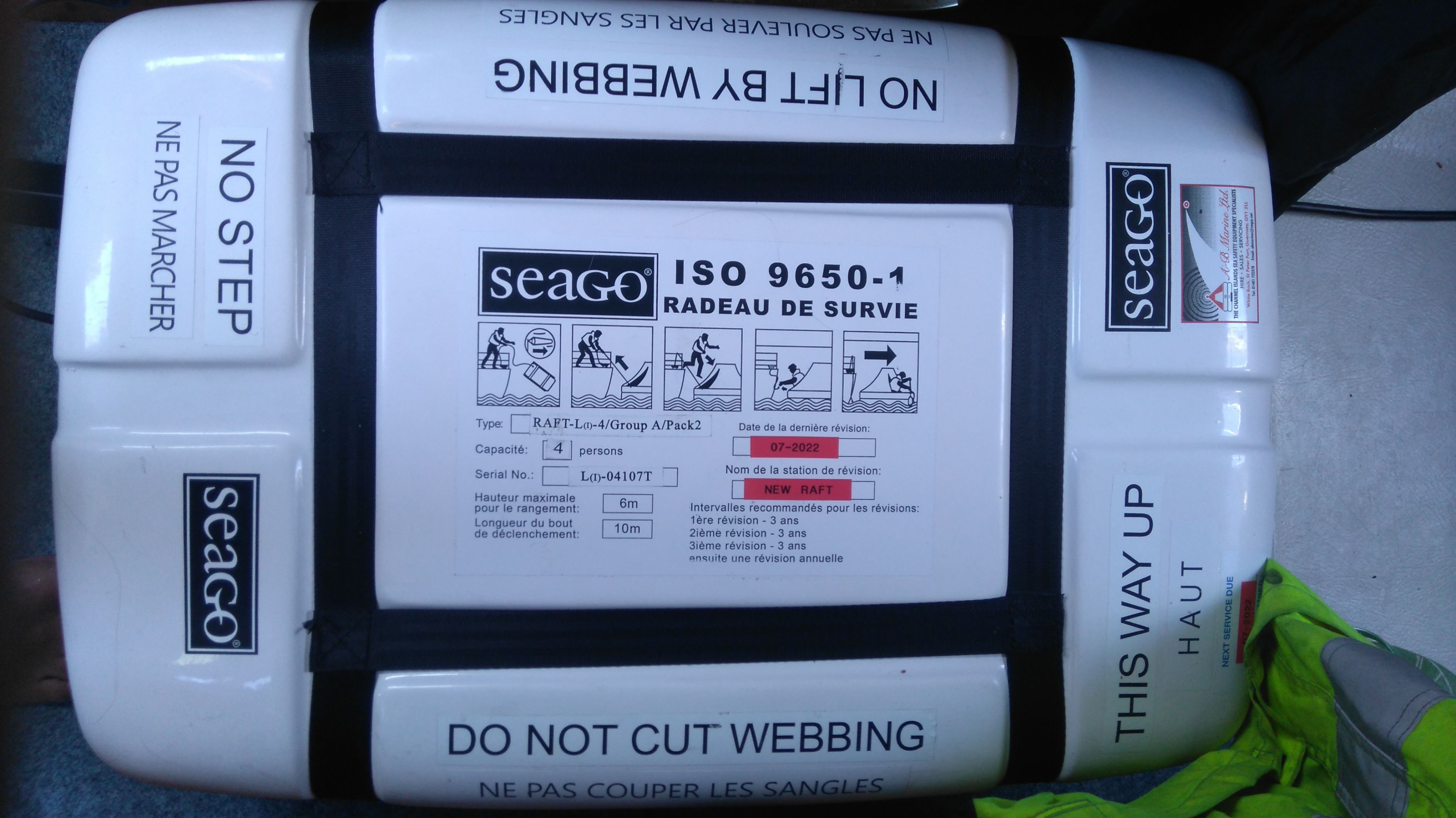

Due to the specific political situation (Guernsey depends on the British Monarch as the heir to the Duchy of Normandy, but is not part of the United Kingdom), Guernsey has certain characteristics of a tax haven, which is why we decided to purchase an ocean rescue raft there. It turns out we don't save as much as we thought, but we wanted to have this raft before we venture into the Bay of Biscay.

After two days, we return back to the continent, to Paimpol. The weather immediately improves and in the sunshine, the town looks very picturesque, although entering here again requires very careful monitoring of the tides - when the water recedes, the only proof that it is possible to reach this place by sea are the channel buoys lying in the mud.

With short jumps we move west. Among the places that impress us, Camaret-sur-Mer should be mentioned. Due to the favorable coastline layout, this place has served fishermen and sailors for centuries. At the breakwater, there are wrecks of trawlers that are no longer in use.

Under the ceiling of the raw Gothic-style church hang models of sailing ships. Inevitably, we ponder those who sailed these beautiful but treacherous and demanding waters before us.

Kamil suspects that one of the bottom scuppers has started leaking. Water gets into the bilge - two buckets every three days. This worries us a lot. We originally planned to end this cruise on the eastern shore of the Bay of Biscay, but we have great winds all the time and reach the marina near the middle of the holiday. Last winter, Kamil did a thorough research of potential "wintering" spots, and with the extra time we have, we could easily sail to another viable location, even in Portugal, except that in many of them boats stay in the water for the winter, which makes the leak deadly dangerous for the yacht.

Naturally, it's quite humid inside the boat overall, so unless it gushes, it's hard to find the culprit. Finally, Mr. Technical Ph.D. finds a way. He lines the bottom of the boat with pieces of toilet paper and observes where it gets the wettest.

It turns out that water is leaking through a fitting from the mechanical log counter that hasn't worked for a long time anyway. To replace the fitting, the boat would have to be hauled out, which would take a few days and cost a lot, so we decide to handle the matter on the water. Kamil loosens the fitting inside the boat and then dives to unscrew it from below. Zuza is poised above, and when water starts squirting in, she plugs the five-centimeter diameter hole with her heel. Zuza remains motionless while Kamil dives repeatedly to clean the bottom around the hole and then fit a new seal. Finally, after one more dive, he inserts the new fitting from below and Zuza tightens it from above. The entire operation took about an hour and went smoothly. The Stubborn stops leaking.

The side effect of the operation was that for the next two weeks, Kama had a new game. She shredded toilet paper and stuffed it everywhere to look for leaks. She didn't want to go on deck at all, sitting inside the yacht, enthusiastically tearing through roll after roll of toilet paper. We wondered if she would have had equally successful holidays locked in the toilet at home?...

We confirm that the Portuguese marina Povoa de Varzim will have a spot for us and decide to cross the Biscay Bay - the Gulf is known for its capricious weather, but we have very good forecasts. Besides, we are now accustomed to sailing. If next year we start "with a bang," seasickness could hit us hard, which can be dangerous and is always very unpleasant. We calculate the time and money and decide to cut through the Bay about halfway. In Port-Haliguen, we are hit by a storm. The wind blows around 8B, and the sea looks really threatening. We are glad to be sheltered in the port.

The next day everything slowly calms down, so we decide to set off for the anchorage at Belle Ile. This way, we will save a lot of time in the morning. Leaving the port always takes a while, and setting off from the anchor takes a few minutes. At sea, it turns out the storm is calming down very slowly - the wind might be weaker, but the waves are large and very unpleasant. We cover about 10 miles in three hours, but we are as exhausted as if we sailed a full day. Fortunately, the anchorage is good, and the weather calms down completely at night, so at least we get a decent sleep.

Afterwards, we set off for Ile d'Yeu, anchor overnight, and head west. We have 350 miles to cover non-stop. The wind is very light, so we even decide to deploy the spinnaker for a moment.

However, we are a bit afraid of that big, strong sail, so we take it down. Once, when we didn't lower it immediately as the wind started to pick up, we had quite a bit of trouble later. Something got stuck at the top of the mast, and the yacht was racing at its maximum speed. At times, we started to lean, and it was scary to climb the mast. Finally, the spinnaker tore, and we managed to control it. Then followed several hours of sewing (which one has to get used to when sailing).

So we may be sailing slowly, but calmly. We have time to fish and enjoy the tranquility of the ocean. Of course, we don't have complete peace of mind on such a long crossing. Even though we know the weather forecast and are equipped with AIS, radio, an ocean raft, and a range of other extremely helpful devices, a shadow of unease always remains. One of the adults must always be at the helm, while the other sleeps or takes care of the child. There's less relaxation than on one-day hops. Kamil, being the most experienced, feels responsible for our safety and, even when it's a clear day and Zuza is at the helm, he can't completely relax and fall into a deep sleep.

Kama is engaged in her favorite activity at the moment, looking for leaks, tearing and stuffing toilet paper everywhere. At a certain point, dolphins swim to us. We see them for the first time on our yacht, so we call Kama to the deck. The kid is accustomed to the fact that something better than just rice or pasta can be eaten when we fish something out. So the dolphins interest her only in this sense - "Dad, give me the rod"... "But one doesn't eat dolphins" we explain. To which Kama replies, "But we have a frying pan and we'll fry them...".

Dolphins are very friendly. They swam beside us, jumping and allegedly reacting to clapping, but we didn't know that at the time. When we sit on the bow, they come very close and watch us. They tilt to the side, just to see us clearly with one eye. However, when Kamil gently touched one, they all immediately fled. They are wild animals, and despite many stories of rescued castaways, they can be dangerous when they feel threatened, especially towards the young (they can bite, as well as ram and break ribs).

Fortunately, the passage is not too long - after two days and eighteen hours we arrive in Gijon.

The marina is large and comfortable. Even though we arrive in the middle of the night, we have no problem parking. After almost three days on the water, Zuza is delighted with the land, and Gijon seems extremely beautiful to her. Kamilka also likes it very much - she is thrilled with the palm trees and runs excitedly along the promenade. We notice that the locals, especially the older people on the benches, pay attention to the running child and look around nervously until they identify the child's parents - nevertheless, if the kid got lost, it would be a big problem - even if she understands English quite well, she wouldn't be able to explain where is she from and how to contact her parents. We promise ourselves that next year we'll make her a Niezgubka (loose-me-not) band - a silicone bracelet with our phone numbers engraved but not painted - from a distance, it looks like a regular bracelet, but in case of loss, the child can get help more easily. Later, we also use the Niezgubka band in Poland multiple times - every time we go to a crowded place. We have agreed with Kamilka that she should look for a police officer, ask for help, and show the bracelet. Fortunately, we have never had to test whether this emergency measure works so far.

After nearly three days of sailing, we rest on land for three days - exploring the city and lounging on the beach.

While in the port, we meet other sailors. The man next to us is planning to sail across the Atlantic alone and then send the boat back to Europe in a container. Such an option never occurred to us, but it's good to know that there is such solution.

Zuza runs to the pharmacy to get constipation medicine. Using a dictionary, she explains the problem, but looking at the picture on the medicine box, she realizes the drug she received is to clear sinuses, while the issue is at the opposite end of the body. The embarrassed pharmacist apologizes profusely. The young man speaks excellent English, but it turns out Zuza used an English word that closely resembles the Spanish term for a cold.

After a longer rest, we head further to Luanco and to an anchorage with a small black beach, so the child can play in the sand.

The beach is okay, but the water temperature in the almost open Atlantic isn't much different from Baltic standards, so longer swims are out of the question. After relaxing in nature, we arrive in Ribadeo, a town inhabited since the Iron Age.

At one time it had strong ties with Eastern Europe, goods from the Baltic passed through it, but later it lost significance in favor of Gijon. The city's former wealth is evident in its beautiful architecture. There are also plenty of small taverns where locals meet for a glass of wine and tapas. We also visit Viveiro but decide to skip a Coruna, spending the next few nights at various anchorages. Since the weather is calm, we go ashore to enjoy the beach and take walks.

August 17th we stop in Baiona. We visit the local fortress and admire the replica of the 'Pinta' - the first European ship to return from America and announce the success of Columbus's expedition. We are somewhat surprised by the relatively small size of the caravel.

One more night at anchor and we reach our port of destination, the marina Povoa de Varzim.

In winter, Kamil has sent emails to all ports across hundreds of miles of coastline, where we could finish that year’s cruise. Prices were higher than in the north, about one and a half thousand Euros. Povoa not only had a convenient location - 30 km from Porto - but also offered a price of 700 EUR. For this money, one could stay on the water or stand on land, only needing to pay extra for a cradle. This did not seem strange after a small town in the Netherlands, where with a stand and everything, a similar amount was paid for wintering. We considered leaving Stubborn in the water, but the thought of a yacht with a hole in the bow seen in Dieppe definitely cooled enthusiasm for this idea.

A walk around the marina confirms the decision not to leave the yacht on the water there. With the typical direction of winter storms, the port is completely open to the waves. Further reading on the internet confirms this. Someone wintered on the water, but six people protected the yacht during each storm. Not for us, since we must spend ten months back at work. So, for the same price, standing on land was offered, only an extra charge for the cradle... And here's the problem. The port was built with EU funding. The ground is the port's. The crane is the port's.Everything is public money. But the yacht stand is rented by only one private company. There used to be two, but there's no contact with the other. The monopolist charges 700 EUR per season on a cradle. So twice as much as the port, parking lot, and crane. Kamil quickly calculates that for half the price, steel and a welder can be bought, so a stand can be made and, next year, it can be sold to someone else. But a pair of experienced Swiss sailors, people who have circumnavigated the world twice, advise against this solution. They have a daggerboard boat that could simply be put on land without any stand, but the question is whether a boat left this way will last until the next year or if an unforeseen 'hurricane' will ruin it, or a small fire might happen...

Overall, the price with the stand was slightly lower than what ports in Spain offered. But such a way of negotiating doesn’t sit with us well. We suspected that when we came next year there could be some additional fees before the boat was put back in water. This time luck was on our side with the weather. The next day was supposed to be calm, which allowed a return on the engine northward to Spain (the wind in this region mostly blows south in summer). So, the next day, we headed towards Spain, close to the shore,- and calling which offers are still available.

The only problem was that the engine shaft seals didn't hold up on the journey north. It was bound to happen eventually. Besides the canals of the Netherlands, we almost didn't use the engine. It is quite old, every year Kamil fixes something in it, we conserve it, and it works. Just during the stretch from Povoa northward, the engine began spewing a liter of oil per hour. We collected everything in plastic bottles and used up the entire supply of fresh oil, but at the very end of the voyage, it wasn't such a problem anymore.

Late at night, we arrived at the Spanish anchorage of Punta Subrido, where we were greeted by the stunning scent of eucalyptus. We reviewed the responses from marinas - Vigo was the first to respond, it was also nearby and had a reasonable price, so we headed there and it turned out to be a good choice.

We had a flight from Porto, so we took the opportunity to explore this beautiful city.

Comments